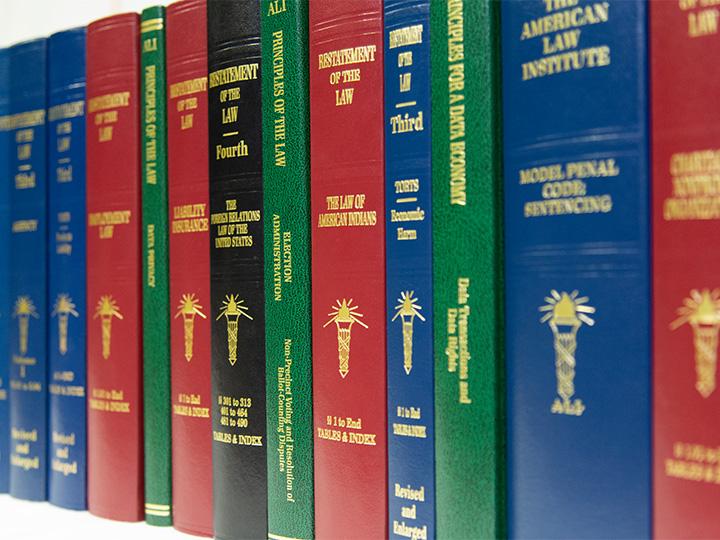

This episode explores one aspect of our ongoing project, Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Concluding Provisions. Specifically, we'll be discussing medical malpractice.

Torts was one of the first Restatements completed by The American Law Institute. Now in the Third series, nearly 90 years later, medical malpractice has never been included in any Restatement series until now. Led by Restatement Reporter Michael Green, the participants will discuss why now is a particularly opportune time for ALI to take on this unruly subject.

Michael D. Green

Michael D. Green is the Bess and Walter Williams Professor of Law at Wake Forest University School of Law. He is a nationally and internationally recognized torts teacher and scholar. In August 2018, he received the ABA's Robert B. McKay Award for outstanding contributions to the field of torts.

He has also received the William L. Prosser Award from the AALS and the John G. Fleming Memorial Prize for Torts Scholarship jointly with Professor William C. Powers, Jr., of the University of Texas. Mike served as Co-Reporter for the Restatement Third of Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm and for Apportionment of Liability with Professor Powers. They were jointly named the R. Ammi Cutter Reporters by the ALI from 2011 to 2015. He currently serves as Reporter for Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Concluding Provisions. He is a member of the European Group on Tort Law, which prepared and published Principles of European Tort Law in 2005. He is a founding member and emeritus Executive Committee member of the World Tort Law Society, an organization of torts scholars from Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Mike regularly lectures in Europe, South America, and China. He is a co-author of a leading Torts casebook and of two advanced torts casebooks. He has written dozens of articles in the tort, products liability, and scientific evidence areas. He is also a co-author of the Reference Guide on Epidemiology, contained in the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, a joint publication of the National Academy of Sciences and the Federal Judicial Center. The Guide serves as a reference on scientific disciplines for federal and state court judges. In addition to his tort and products liability scholarship, he has written extensively about toxic torts and the issues of causation and apportionment that arise in those cases. He has an instrument and commercial pilot's license. Mike received his bachelor’s degree from Tufts University and holds a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He and his wife, Carol, have two sons and a daughter and four grandchildren.

Mark A. Hall

Mark A. Hall is the Fred D. and Elizabeth L. Turnage Professor of Law and Director of Health Law and Policy Program at Wake Forest University School of Law. He is one of the nation's leading scholars in the areas of health care law, public policy, and bioethics.

The author or editor of twenty books, including Making Medical Spending Decisions (Oxford University Press), and Health Care Law and Ethics (Aspen), he is currently engaged in research in the areas of health care reform, access to care by the uninsured, and insurance regulation. He currently serves as Associate Reporter for ALI’s Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Concluding Provisions. Mark has published scholarship in the law reviews at Berkeley, Chicago, Duke, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Stanford, and his articles have been reprinted in a dozen casebooks and anthologies. He also teaches in the University's Graduate Programs for Bioethics and its MBA program, and he is on the research faculty at the Medical School. Mark regularly consults with government officials, foundations and think tanks about health care public policy issues. Mark received his bachelor’s degree from Middle Tennessee State University and holds a J.D. from University of Chicago Law School.

Laura Sigman M.D., J.D.

Laura Sigman, M.D., J.D., is an Emergency Medicine physician, Director of Legal and Policy Coordination of Emergency Medicine for Children’s National Health System, and Principal and Founder of MD|JD Associates. She excels at providing in-depth analysis and advice on issues that bridge law and medicine.

Dr. Sigman's professional experience includes managing legal and policy issues for a hospital emergency department; conducting investigations of adverse events and malpractice cases and developing preventive risk management strategies; counseling physicians involved in adverse events and malpractice cases; successfully testifying for the passage of health law bills; advising Congressional candidates on health policy; and litigating complex health law cases with the U.S. Department of Justice. Her rigorous training at institutions including Harvard Law School, the University of Chicago Medical School, and Johns Hopkins Hospital is balanced with a collaborative, team-building interpersonal approach. She speaks frequently on legal and risk management issues relevant to clinicians and on best practices surrounding medical errors and adverse events. Dr. Sigman received her bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College, her J.D. from the Harvard Law School, and her M.D. from the University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine.

Shanin Specter

Shanin Specter is founding partner of Kline & Specter, P.C. and a one of the premier trial lawyers in the U.S. He has obtained more than 200 jury verdicts and settlements in excess of $1 million and more than 50 case resolutions—16 verdicts—greater than $10 million.

Among his verdicts are $153 million against a major automaker and $109 million against an electric power company. Shanin's legal victories have included news making, industry-changing cases involving medical malpractice, defective products, medical devices, premises liability, motor vehicle accidents and general negligence. Beyond winning substantial monetary compensation for his clients, many of Shanin's cases have prompted changes that provide a societal benefit, including improvements to vehicle safety, nursing and hospital procedures, the safe operation of police cars, training for the use of CPR at public institutions, and inspections, installation and maintenance of utility power lines. The Goretzka case even spurred the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission to create a new Electric Safety Division to investigate reported electrical injuries. Similarly, his lawsuit—plus television appearances calling for action—on behalf of the victims of a fire escape collapse helped move the City of Philadelphia to enact an ordinance requiring all fire escapes to be regularly inspected by an independent structural engineer. Shanin earned his law degree from the University of Pennsylvania and an LL.M. with First Honors from Cambridge University and has compiled a lengthy record of professional accomplishments and accolades. He is a member of the Inner Circle, a group of the best 100 trial lawyers in the country. He is a member of The American Law Institute. Shanin was featured on the cover of SuperLawyers magazine, in which the independent rating service called him one of the most celebrated and respected catastrophic injury litigators in the country.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on Reasonably Speaking are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of The American law Institute or the speakers’ organizations. The content presented in this broadcast is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. Please be advised that episodes of Reasonably Speaking, explore complex and often sensitive legal topics and may contain mature content.

Introduction: Thank you for joining us on this episode of Reasonably Speaking. Today we’re going to explore one of our ongoing projects, Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Concluding Provisions. This is one of the remaining projects in the Restatement Third Torts series. That once approved will entirely supersede the Restatement Second of Torts. Specifically we’ll be discussing medical malpractice. Before we begin, let me introduce our participants. Moderating the conversation is project Reporter Michael Green of Wake Forest Law. Mike Green is an internationally recognized torts teacher and scholar. In August, 2018 he received the ABAs Robert B. McKay award for outstanding contributions to the field of torts. Mike served as Co-Reporter for the Restatement Third of Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm and for apportionment of liability with professor William Powers. He is a founding member of the World Tort Law Society. Joining Mike in the studio is one of the project’s Associate Reporters, Mark Hall of Wake Forest Law and Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Mark Hall is one of the nation’s leading scholars in the areas of health care law, public policy and bioethics, the author editor of 20 books including making medical spending decisions and healthcare law and ethics. He is currently engaged in research in the areas of healthcare reform, access to care by the uninsured and insurance regulation. We have two additional participants joining by phone. The first is Dr. Laura Sigman of Children’s National Health System. Dr. Sigman as an expert in medical law, policy and risk management. She is a practicing physician and a licensed attorney. With her unique multidisciplinary perspective, she devises strategic solutions to drive improvements in healthcare. She’s frequently consulted on a range of healthcare and compliance questions and has led legislative initiatives as well as testified for the successful passage of health-related bills.

Also on the phone is Shanin Specter. Shanin is a preeminent American trial lawyer. He is a founding partner of Kline & Specter, one of the leading catastrophic injury firms in the United States. He has obtained numerous jury verdicts and settlements in cases involving medical malpractice, defective products, medical devices, premises liability, auto accidents, and general negligence. He is a member of the Inner Circle of Advocates whose membership is limited to the top 100 plaintiff’s attorneys in the United States. I will now turn the microphone over to Mike Green.

Michael Green: Good morning. This is Mike Green and thank you for joining us on this podcast where we’re going to talk about the American Law Institute and its work and particularly its work on medical malpractice. A little known fact is that although we have had now almost a hundred years of a Restatement of torts, 90 years of a Restatement of torts the Restatements that preceded us have never addressed the matter of medical malpractice, which is a major area of tort law for reasons that are obscured by history the ALI has ignored medical malpractice. But it’s changed its tune and is now beginning the process of doing a Restatement of medical malpractice. Mark, do you have any thoughts about why now is a particularly opportune time for the American law Institute to take on this unruly subject?

Mark Hall: Well, that’s a good question, Mike. And I asked myself that when invited to participate, why now and why me? I mean, the strongest reason being that this is certainly one of the most major, perhaps the major area of tort litigation that the Restatement has not covered. And it’s sort of glaring by its absence and here at the end of a 20 year updating of tort’s third no better time than to step up and cover this area. But more than that, a lot is going on in the medical field that relates to or is informed by liability policy. Daily we hear about controversies in developments in medicine. As we tape this of course, we’re in the throws of a Coronavirus pandemic that’s rich with learning opportunities, I suppose with regard to liability and responsibility, but more on a more routine day to day basis just about every medical encounter has a variety of fundamental legal questions in terms of the structure of the relationship and the interaction and the duties that flow from that.

And although every state has rich case law on those duties and responsibilities. So for the most part, this is not an area that’s lacking guidance. A lot of that case law was developed over the past 150 years in the circumstances and the nature of medical practice have changed fundamentally over that time. And so it’s a very apt point at which to re-examine the very core fundamental principles to say, do these still make sense because aspects of medical treatment and the doctor patient relationship are timeless and universal, or should we begin moving towards some adjustment of some of these principles because they assume certain basic conditions of society and cost and medical technology is such that they have changed since their initial adoption.

Green: Shanin you have an extensive history so to speak on the ground with medical malpractice. If Richard Revesz, the director of the ALI had called you a couple of years ago and said, “Shanin, we’re thinking about doing a Restatement that will cover medical malpractice,” What advice would you have given to the ALI about the prospect of such a project? I’ll rephrase the question. Let’s start with the first potential question that I might have asked. Would a medical malpractice Restatement be useful and wise for the ALI to take on?

Shanin Specter: I think it would be useful for several reasons. The first is that we don’t, to my knowledge, have a comprehensive statement of the law nationally as the medical malpractice and looking at the draft, the draft is helpful to me, both as a practitioner and also as a teacher in consolidating my thinking as to what courts around the country believe on these various subjects and whether there is a consensus viewpoint around the country on these subjects. Secondly, there are many States in the United States that have a poorly developed legal system as it relates to medical malpractice because they simply haven’t seen that many medical malpractice cases wind their way through the courts.

Specter: So having a national statement may prove very useful to those lawyers and judges. I think that for a large State with a very well developed set of case law, the project might be somewhat less important, but it still is important in the sense that some of those States are outliers with respect to some of these issues and their status as outliers becomes more clear when we have a Restatement that we can see what the national position is on some of these issues.

Green: Dr. Sigman do you agree with Shanin about the utility of a final version of a Restatement of medical malpractice?

Laura Sigman: I do. I think it’s really useful for there to be a sort of centralized summary of malpractice law principles that’s accessible both to lawyers and while doctors necessarily not that wouldn’t necessarily be inclined to read the document. I think having that knowledge out there and more available in a consolidated way provides really useful information to guide the practice of medicine and a part of the legal system that causes significant anxiety in medical practitioners. And also drive a lot of what’s referred to as defensive medicine and practices and having more clear eliminations on what truly can be enforced in terms of medical liability might lead to some additional clarity on for providers to guide their practices.

Green: So, Dr. Sigman, you said that it was unlikely that doctors would read such a document that seems a pretty good prediction. Can you think of ways in which doctors might become interested in or informed about the existence of such a Restatement in well in whatever form or our program that, that might exist that for doctors?

Sigman: Sure. So I don’t mean to say that doctors aren’t interested in the topic. I think this is a huge area of interest for medical providers and one that they have very little knowledge and education on. I think the illegal treatise is what’s less likely to be comprehensible to physicians. I think a summary version of this Restatement would be an excellent way to communicate with doctors about it and perhaps targeting a medical journal as a source of publication for a summary of the many useful pieces of information that has been brought up in this Restatement would be a great way to reach the medical field.

Green: It may take some extraordinary efforts. On a personal note my daughter is a pediatrician and I have never been able to get her to read anything in the form of a Restatement in the past. So we may need to work hard to get pediatricians and doctors.

Sigman: While, that may be true. I would challenge you that if you talk to her about what she does in her practice and how that might expose her to liability you would, you would very quickly get her attention and bring up the case about a pediatrician being sued and how that might impact her practice and you might catch some more interest that way.

Green: I still recall the telephone call from her as a young resident telling me that she had been named in a medical malpractice suit. It was not a happy conversation. Mark are you feeling good about the prospect that both the medical field and the practicing bar thinks that what you’re doing is a useful exercise?

Hall: Certainly I feel like there’s an enthusiastic audience for any and all of the work of the ALI, but certainly in the field of this prominence where the ALI has not convened before. I’m anticipating a very eager interest in uptake of our final product, which poses challenges in doing the work. First of all, Shanin has said that there’s a lot of case law development across the country, particularly in the larger States. And so given that variety it’s a learning curve for me to figure out what is the role of a restater when you’ve got a third of the States going one way and a third of the state’s going in another way. And the third we don’t know yet.

But I do feel like there’s great opportunities in areas where I can anticipate more focus in the future on certain issues that haven’t been well developed really in any States, maybe a smattering of development or some sort of early thinkers or leaders where we can step in and certain smaller pockets of the law, not the core doctrine, but sort of elaborations of the core where I think the ALI Restatement could serve some of its longstanding traditional role of really being a leader that points towards a development of best thinking and best principles that are grounded in the established principles, but then elaborate more or apply them in important recurring areas. And so identifying some of those important hotspots if you will, or areas that need more development I think is one of the exciting challenges that I have.

Green: So let me take that last comment about hotspots and let me ask all three of you what are the two or three particular most important issues where having a Restatement that attempts to make sense of and provide coherence to that subject? What are the important ones? Shanin, you have thoughts on that?

Specter: Well, it’s a good question. So I’ll start with that I think that of the topics you’ve laid out, I think the ones that have the greatest importance would begin with causation loss of chance, and that has applicability beyond medical malpractice to the entire tort field, although we think about it usually in a medical malpractice context.

Green: Shanin, can I interrupt you? Shanin, can I interrupt you at this point-

Specter: Yes.

Green: ... and just ask you to tell our audience a little bit more about what you’re referring to when you say loss of chance?

Specter: Sure. So some States take the position that if the defendant’s negligent conduct in increase the risk of the harm sustained by the plaintiff, that the plaintiff has met her burden of proof and may proceed to have the jury make the determination as to liability. And some States take a position that the plaintiff must show that much for the negligence of the defendant and the plaintiff would not have sustained the injury complained of. And some States take a position somewhere in between. And there’s been a lot written on this subject, usually in a medical malpractice context, of a scholarly nature. It’s a hotly debated concept. Again, the States take very different positions. New Jersey for example, recognizes loss of chance, but then reduces the verdict by the chance that the jury finds that the harm would have occurred anyway, even if the defendant had not been negligent.

Pennsylvania recognizes loss of chance but does not make that reduction. Some other States don’t recognize loss of chance at all as an approach. It’s a very difficult issue and a very interesting issue. So I think that is a very, very good issue. Second issue is institutional liability, so called corporate liability. And to briefly state that principle, and this is a principle that’s developed in the law over the last three decades or so. And that is that a hospital owes a non-delegable duty to assure the safety of the practice of medicine within its four walls. And some States take a broad approach to that and some States don’t recognize it at all.

And some states take an in between position. And when I say some States don’t recognize it at all. Some States take the position that with respect to, for example, independent contractor positions that the hospital does not stand behind them as a legal matter and they are not essentially the guarantors of that quality of care provided by their other practitioners within their four walls. So, that’s a very short summary of that issue. There are many other tentacles to it as relates for example, to equipment, facilities and the like. I think that would be a very good topic to address.

Green: Okay. Dr. Sigman, do you have thoughts about this areas where a malpracticeRestatement would be particularly useful for physicians?

Sigman: Yes. I think there are several areas of trends in the medical field where having such a Restatement may provide excellent guidance as evolutions in medical care continue. In terms of the institutional liability that was just mentioned, I think we’ve seen a great trend of more doctors being employed by institutions and away from the small private practice model. And that as we define that institutional liability more concretely, it will be very useful as we continue to see more, more younger doctors coming out and being employees of institutions rather than practicing on their own. We also have trends where we’re moving towards more accessible medical care, urgent cares have seen an enormous amount of growth in the past 10 years or so and there’s increased practicing by physician assistants and nurse practitioners some of whom are supervised by physicians depending on state regulations and some of whom can practice independently.

And I think the guidelines provided in Restatement will help to eliminate what the liabilities are for these types of practices. Related to that is the establishment of the physician patient relationship that the Restatement will address and looking at what is required to establish a doctor patient relationship or nurse practitioner patient relationship, particularly as we move towards more prevalence of telemedicine and telemedicine programs that cross state boundaries as well as towards more use of the sort of retail based urgent cares where there’s not an established relationship between the doctor and the patient as there might have been in traditional family practices.

Green: Great. Mark, I wonder about your thoughts about these subjects, maybe other subjects that you think are particularly critical and how you’re feeling about restating the law about changes in healthcare delivery. Where I suspect the case law is going to be very sparse if not non-existent.

Hall: Well, I look to guidance from my senior ALI Reporter colleagues and about how to walk that tight rope. And so I’m trying to learn best practices as a Reporter in terms of what’s appropriate for black letter and what’s appropriate for comments and what’s appropriate for Reporters’ Notes. And so in general to address the more general question, if there’s a particular application does go into a retail clinic a drug store where you see a nurse practitioner create an ongoing treatment relationship. That’s the kind of thing that might be used as the basis of an illustration or might be addressed in a comment but is unlikely to be become what we call black letter law. The black letter law will most likely stick to broader general principles, but then the comments are a great place to dig into these instead of using examples from 150 years ago.

Which is also still good to do to remind people where the law came from. Use examples that are very, very current. I’m encouraged by the list of examples that our two colleagues have just listed because they are all either on my mind or actually on paper to some extent. And each are topics that I had also considered as important to address in one fashion or the other with regard to any other additional topics. I think there’s one more elephant in this room and that is the economics of health care, and not only is healthcare increasingly expensive and that’s been true for as long as I’ve been Alive and perhaps throughout history, but more so than in the past those expenses are coming to be borne by patients. And to what extent the costs of care born by patients, or potentially born by insurance companies, factor in appropriately or inappropriately to either decisions about medical care or conversations about medical care. I think is an ever present issue that’s going to grow in importance on which we have remarkably little guidance from the case law. And so I feel like it’s an opportunity to at least lay some groundwork of basic principles by which courts can begin to think about that.

Green: Mark, I have another question I’d like to ask you. What are you going to do as a Reporter when, as Shanin was suggesting you do all your research across all 51 jurisdictions in the United States and discover that they’re split. And I think the math works out 17, 17 and 17. That is one third, one third, one third. What do you do to restate law that has not coalesced and found some majority at least majority view?

Hall: Well, I think each circumstances is different. The current draft, which isn’t going to be the focus of our conversation because by the time it airs or by the time someone listens, the current draft will likely have changed. But it wrestles with that problem with regard to informed consent and the basically 50-50 split between the two different ways of framing the position’s obligation to disclose risks. Shanin talked about the loss of chance and sort of that’s more of a three way split than a two way split.

Sometimes the nature of the topic is such that arguments are strong on both sides and court seemed pretty well settled and one side or the other, there’s probably not going to be a lot of movement. Maybe just some fine tuning that is appropriate to sort of lay out both options. Sometimes it might be possible to find a hybrid that kind of satisfies most of the concerns on both sides, but minimizes some of the troubles of the more extreme positions. And so if that sort of Solomonic splitting of the baby option is available, then that’s another way to consider it. I think sort of those are two basic approaches that can be taken and which approach is best I think depends on the particular topic. And also strongly depends on the advice that we receive from our well-chosen Advisers.

Green: So Shanin and Dr. Sigman I want to ask you to consider another hypothetical phone call. And it’s professor hall who calls you. And he says listen, "There are people on both sides of a number of issues and they have strong feelings about which direction the Restatement should go on." For example last chance. And he says to you, “What advice do you have for me about how to deal with that strong opposing views on a given issue?”

Specter: Well I believe that the Restatement should not take a position on what the law is when there is no consensus around the country on what the law is. But rather the Restatement would be helpful to the bench and the bar and to scholars if they were to identify the split, discuss how many States take one position or another or a third or no position at all, and provide the cases that have the most intellectually vibrant approaches to the varying positions that a judge or a practitioner or a scholar can read that and come to her own conclusion as to what she believes in the direction of law should be, or if they’re an advocate and they can utilize those arguments in advocacy.

And I think that some might find it to be unsatisfactory because there’d be no clear statement, but we are not a legislature and it’s important that we retain the respect of the legal profession and I think we would lose respect if we were to seek to act and say what the top of the law is, or even to say what the law should be when no clear consensus has emerged.

Sigman: I very strongly agree with that from a medical provider perspective, thinking about the idea of summarizing law when it very much has variability between different states would make my hair stand on them because if I’m practicing in... so I live in the DC area if I practice in DC and I’m advised about my liability for certain actions or my responsibilities, for example, for informed consent in a way that doesn’t apply to my jurisdiction, that certainly would put me at risk. And even though as we mentioned, doctors aren’t necessarily going to be reading the Restatement. Obviously the malpractice attorneys are. And as that trickles down to inform medical providers about their practices, it would have a crucial effect on a doctor’s practices and liability. So I think it’s very important that the three statement addresses the variability in law across States in this area that is largely case law based and doesn’t make generalizations or take positions on what the

law ought to be. Well those might be certain interesting components to include. I think making clear the variability between States is extremely important.

Green: Your comment reminds me of something that would be very important if non- lawyers are going to see anything in a Restatement, it be important to explain to them that the Restatements are not law and they don’t state what anyone who is addressed in them should do. The source of law is courts and legislatures and administrative agencies not Restatements. Restatements only become the law when a court decides to adopt it, not simply by the force of what it says. And particularly for non-lawyers, it would be important to emphasize that. Mark your thoughts about this advice you’ve just been given?

Hall: Yeah, and that advice is somewhat different than the advice I’ve received from my senior ALI colleagues. Which reminds me of two points. One is that this is not ... although it’s Restatement of the law, it’s not the law. The second is the aim is not to be a treatise to simply catalog the law. The aim is really sort of to provide guidance. What’s your best thinking? And I think to use the medical analogy and I also serve in half of my academic appointment at the medical school. There’s ways of driving consensus statements about best practices in medicine that can be influential even though not everyone follows them. And even though there’s some differences of opinion, so the ALI membership is a tremendous and impressive sort of brain trust of experience and knowledge and thinking and deliberation.

And many people, and I agree. I think it would be a waste of that resource if opportunities weren’t taken when they presented to do a bit more than simply cataloging what courts have done and that bit more is to really point in the direction of where the membership collectively thinks is the best thinking. And sometimes it is the case that it just isn’t clear, which is the best course in which case simply more or less cataloging or summarizing is the right course.

But oftentimes sorting through the various positions is possible to discern one established position seems to be the better of the ones collectively to the membership or there might be a variation that seems to satisfy a majority of the concerns. And so searching out that sort of vein of gold I think is, is always something that my predecessors and other Restatement workers have searched for that I’ll continue to do so. Mike has reminded me a respected and revered colleague an academic or a judge who you’ll have to tell me the line about the job of restater was to-

Green: I was thinking that, yeah.

Hall: Fill in the void Mike.

Green: So, this seems an appropriate point to explain the direction to Reporters that actually hangs on the wall of the ALI fourth floor conference room. And that certainly has influenced me in the work I’ve done on Restatements in the past. It was issued by Herb Wechsler, a former director of the ALI. And it explains that Restatements are not simply what they sound like they are, which is to catalog restate. And what Wechsler said is, “We should do what a wise judge would do fully informed of all of the precedents, but bound by none of them.” And that captures what I think the ALI tries to do sometimes not adopting a majorityposition because there’s a trend in the other direction. Often determining a majority or minority is fruitless because the case law is so confused. And so looking for coherency and maybe sometimes as Mark suggests best practices is a lot of what the ALI tries to do in Restatements. At this point I’d like to ask each of Shanin and Dr. Sigman for concluding thoughts. We will not let professor Hall have that option.

Specter: Well, I’d like to comment on what you both just said about what is the goal of the Restatement. I certainly agree that the Restatement should be a statement of what is the best course or what a wise judge would do, where that is reasonably discernible without doing damage to other important principles. That seems to be easiest to achieve in an area of law that has not been plowed deeply in many places with extraordinarily varied results. And so I think about the Restatement as it relates to product liability. If you think about the law towards the two most controversial areas are product liability and medical malpractice.

And we had the Restatement of Torts Second on product liability in 1965 and it was adopted reasonably quickly by a vast majority of States and then a lot of controversy erupted largely between warring segments of the bar and also interests beyond the bar. Manufacturers, consumers and the like. And we ended up with a Restatement of Torts Third adopted in 1998 which landed like a thud and it’s been adopted by only 12 States in the intervening 22 years. That tells us something, I think that is, is predictive or how far we could we can productively go in medical malpractice because we have a lot of the same obstacles todiscerning the best course or a wise judge in medical malpractice that we would in product liability.

Green: Dr. Sigman?

Sigman: I think those are excellent points. I also think that having this guidance at this time is particularly pertinent as the medical field has gone through and continues to go through so many changes both internally and in terms of healthcareinsurance and the accountable care organizations and different types of trends to be more open and honest in our communications in healthcare including through nationally backed disclosure programs that encourage physicians to be open and honest when mistakes occur.

As those trends progress, I think having the Restatement guiding the history of law and providing guidance on how the best scenarios in law should play out will be essential as we face new challenges and obstacles both in terms of patients having more empowerment to make their own decisions and how that interplays with the informed consent as well as we fragment the provision of medical care through different urgent cares and sub-specialists and telemedicine. So I think this is great timing in terms of having a Restatement regarding medical malpractice and liability in terms of going forward and sort of a new frontier of medicine that we’ve approached in the digital age.

Green: Thank you. Since professor Hall has me in a choke hold, I’m going to defer and let him have the last word here. Nope. Okay. He’s actually, he’s released his show called I can now breathe and thank everyone who has listened all the way through this podcast for staying on and hearing about the plans of the ALI in this most interesting area of torts.

Outro: Thank you for tuning in to Reasonably Speaking, visit ALI.org to learn more about this important topic and our speakers. Don’t forget to subscribe so you never miss an episode. Reasonably Speaking is produced by The American Law Institute with audio engineering by Kathleen Morton and digital editing by Sarah Ferraro. Podcast episodes are moderated by Jennifer Morinigo and I’m Sean Kellem.