Absentee Balloting: Preparing for the November Election

In its April 2020 primary election, Wisconsin experienced serious problems in its absentee balloting processes, which led to a federal court case (RNC v. DNC) that the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately resolved on election eve. The problem was that in the face of the current pandemic, the number of voters who requested an absentee ballot overwhelmed the election officials’ ability to get the ballots to the voters in time to cast them. The result was the disenfranchisement of tens of thousands of Wisconsin voters, controversy over the federal courts’ ability to remedy this disenfranchisement, and confusion of the voters. But that Supreme Court decision has done little to solve the problem or to reduce the possibility of an analogous controversy in the future. Indeed, this podcast will consider whether the risk of a similar problem in November is every bit as great. For instance, consider the challenge that would confront Pennsylvania – already taxed by having to administer a new mail-in voting law that for the first time will allow any voter to request an absentee ballot – if an outbreak or resurgence of COVID-19 occurs in Philadelphia in the weeks prior to Election Day.

In the face of a surge in requests for absentee ballots that completely overwhelms state election officials, how should our legal system respond? Should a state court order Pennsylvania election officials instead to accept write-in absentee ballots from these voters? Or to accept ballots that arrive up to seven days after Election Day? Or would such an order violate the Due Process Clause? And could a controversy over this scenario result in Pennsylvania submitting two competing slates of presidential electors to Congress?

Edward B. Foley

Edward (Ned) B. Foley is the Charles W. Ebersold and Florence Whitcomb Ebersold Chair in Constitutional Law and the Director of Election Law at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law.

In January 2020, Ned published a new book, Presidential Elections and Majority Rule: The Rise, Demise, and Potential Restoration of the Jeffersonian Electoral College. His book Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States was published by Oxford University Press in December 2015.

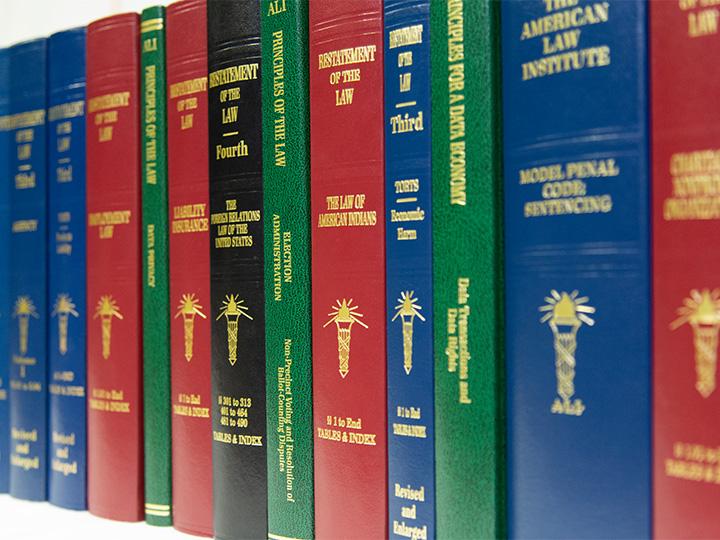

He served as Reporter for The American Law Institute’s Principles of the Law, Election Administration: Non-Precinct Voting and Resolution of Ballot-Counting Disputes.

While he has special expertise on the topics of recounts, he is conversant in all topics of election law, including redistricting and campaign finance, and recently co-authored a casebook Election Law and Litigation: The Judicial Regulation of Politics (Aspen 2014), which covers all aspects of election law. He and his casebook co-authors also have a contract with Oxford University Press to write a treatise on election law—remarkably the first of its kind in the United States in over a century. He is also a co-author of From Registration to Recounts: The Ecosystems of Five Midwestern States (2007).

Ned has taught at Ohio State since 1991. Before then, he clerked for Chief Judge Patricia M. Wald of the U.S. Court of Appeals and Justice Harry Blackmun of the United States Supreme Court. In 1999, he took a leave from the faculty to serve as the state solicitor in the office of Ohio’s Attorney General. In that capacity, he was responsible for the state’s appellate and constitutional cases.

Ned received his B.A. from Yale College and his J.D. from Columbia Law School.

Steven F. Huefner

Before joining The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law faculty, Steve Huefner practiced law for five years in the Office of Senate Legal Counsel, U.S. Senate, and for two years in private practice at the law firm of Covington & Burling in Washington, D.C. He also clerked for Judge David S. Tatel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and for Justice Christine M. Durham of the Supreme Court of Utah. Steve was a Harlan Fiske Stone Scholar at Columbia Law School, where he served as head articles editor for the Columbia Law Review.

He served as Associate Reporter on The American Law Institute’s now completed Principles of the Law, Election Administration: Non-Precinct Voting and Resolution of Ballot-Counting Disputes.

Steve has published a number of articles and one book, From Registration to Recounts: The Election Ecosystems of Five Midwestern States, co-authored with his Election Law colleagues. His research interests are in legislative process issues and democratic theory, including election law. He is conversant in Japanese, spent one summer working for a Japanese law firm, and remains interested in Japanese law.

Steve is director of Clinical Programs at Moritz, as well as director of the Legislation Clinic. He teaches Legislation, Jurisprudence, and Legal Writing.

Steve received his B.A. from Harvard College and his J.D. from Columbia Law School.

Justin Levitt

A nationally recognized scholar of constitutional law and the law of democracy, Justin Levitt recently returned to Loyola after serving as a Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

At DOJ, he primarily supported the Civil Rights Division’s work on voting rights and protections against employment discrimination (including LGBT rights in the workplace). Justin has published in the Harvard Law Review, the Yale Law and Policy Review, the Columbia Law Review, the Georgetown Law Journal, the William & Mary Law Review, the peer-reviewed Election Law Journal, and the online publications of the flagship law reviews at Yale and NYU, among others. He has served as a visiting faculty member at the Yale Law School, at USC's Gould School of Law, and at Caltech. He was honored to receive Loyola's Excellence in Teaching Award for 2013-14. Justin has been invited to testify before committees of the U.S. House and Senate, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, several state legislative bodies, and both federal and state courts. His research has been cited extensively in the media and the courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. He maintains the website All About Redistricting, tracking the process of state and federal redistricting around the country, including litigation. Justin served in various capacities for several presidential campaigns, including as the National Voter Protection Counsel in 2008, helping to run an effort ensuring that tens of millions of citizens could vote and have those votes counted. Before joining the faculty of Loyola Law School, he was counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, for five years. He also worked as in-house counsel to the country's largest independent voter registration and engagement operation, and at several nonprofit civil rights and civil liberties organizations. At Loyola, Justin established the Practitioner Moot Program, a complimentary service to the community allowing attorneys with pending appellate matters to practice their arguments before faculty experts and experienced advocates. Under the program, Loyola has hosted recent moots for cases later argued in the U.S. Supreme Court, the Ninth Circuit, the California Supreme Court, and the California Courts of Appeal, among others. Justin served as a law clerk to the Honorable Stephen Reinhardt of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. He holds a law degree and a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard University, and was an articles editor for the Harvard Law Review. He is admitted to the bar in California, New Jersey, New York, and the District of Columbia, and to the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. Courts of Appeal for the Fourth Circuit, Ninth Circuit, and Eleventh Circuit, and the U.S. District Courts in the Central District of California and Northern District of Florida.

Lisa Marshall Manheim

Lisa Manheim writes in the areas of constitutional law, election law, and presidential powers. Her scholarship has been published in the University of Chicago Law Review, the Iowa Law Review, the Supreme Court Review, and other leading academic journals. These works explore questions of federalism and institutionalism in the context of the judiciary.

Lisa’s courses include Constitutional Law, Election Law, Legislation, and Federal Courts. She is a three-time recipient of the Philip A. Trautman Professor of the Year Award given by the student body. Lisa earned her B.A., summa cum laude, from Yale College and her J.D. from Yale Law School, where she served as Managing Editor of the Yale Law Journal. After graduating from law school, Lisa clerked for Judge Pierre N. Leval of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and Justice Anthony M. Kennedy of the United States Supreme Court. Prior to joining the faculty at the University of Washington, Lisa worked as an associate at Perkins Coie LLP, where she specialized in appellate practice, commercial litigation, and political law.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on Reasonably Speaking are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of The American Law Institute or the speakers’ organizations. The content presented in this broadcast is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. Please be advised that episodes of Reasonably Speaking, explore complex and often sensitive legal topics and may contain mature content.

Introduction: Thank you for joining us for this episode of Reasonably Speaking where we'll explore how our state election officials and our legal system can plan now to respond to the expected surge in requests for absentee ballots for the November election. Our panelists today are all experts in the area of election administration. Our first panelist, Ned Foley, is a professor as well as the director of election law at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. In addition to teaching, Ned is a nationally recognized author and scholar. His latest book titled Presidential Elections and Majority Rule: The Rise, Demise, and Potential Restoration of the Jeffersonian Electoral College was published earlier this year. Ned also served as the Reporter on The American Law Institute's Principles of the Law Election Administration: Non-Precinct Voting and Resolution of Ballot Counting Disputes.

Our next panelist, Justin Levitt, of Loyola Marymount University Loyola Law School is a nationally recognized scholar of constitutional law and the law of democracy. He previously served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Civil Rights Division of the US Department of Justice. At the DOJ, he primarily supported the Civil Rights Division's work on voter rights and protections against employment discrimination. He served in various capacities for several presidential campaigns, including as the National Voter Protection Council in 2008, helping to run an effort ensuring that tens of millions of citizens could vote and have those votes counted.

Our final panelist, Lisa Marshall Manheim, is the Charles I. Stone Associate Professor of Law at the University of Washington School of Law. She writes in the areas of constitutional law, election law, and presidential powers. Her recent articles include "The Elephant in the Room: Intentional Voter Suppression and the forthcoming Presidential Control of Elections." The monitor for today's episode is Steve Huefner, a colleague of Ned's at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. Steve also serves as the director of clinical programs at Moritz as well as the director of the Moritz Legislation Clinic. He previously practiced law for five years in the Office of Senate Legal Counsel, US Senate. His research interests are in legislative process issues and democratic theory, including election law. He served as the Associate Reporter on The American Law Institute's Election Administration Principles. I will now turn over the microphone to Steven.

Steven F. Huefner: So Justin, Lisa, and Ned, it's great to be with you today. The topic of our conversation today really is primarily the legal issues that might arise surrounding what we expect to be a dramatic increase in the amount of voting by mail in the general election in November. Before we begin talking about that general topic, I thought it might be worthwhile to situate in the broader context. What we're talking about is voting by mail processes, not all vote by mail processes, and there's an important distinction. All vote by mail involves a system in which the local election jurisdiction is sending a ballot to all registered voters. That's not what we're talking about.

We're talking about what instead traditionally we have referred to as absentee voting, although today absentee voting in almost two-thirds of the states is something that's available to anyone who desires to vote that way, whereas historically it had been limited to people who could provide some kind of excuse or justification for an absentee ballot. Of course, there are many options that states can consider in how to implement voting by mail or no-excuse absentee voting. How to do that well has been the subject of considerable attention in the past decade before COVID-19 hit, including by The American Law Institute in its Principles of the Law, Election Administration project.

But what we'd like to talk about today are the complications to voting by mail that have been introduced by COVID-19 because of the dramatic increase in the number of voters who want to take advantage of that mode of voting. We've seen in the primary elections already that it's been difficult in many states for the election administrators to handle that dramatic increase. With the November election now less than five months away, time is running short for both administrative apparatus as well as some of the legal constraints to make adjustments and to how voting by mail in a dramatically increased quantity might occur.

Earlier this month, Georgia experienced what by all accounts was a real meltdown in its primary election maybe primarily with respect to in- person voting, although they also had some problems with their mail-in voting. Of course, when you see things like what happened in Georgia, you know that that's going to push even more people to want to vote by mail. Of course, long before the problems in Georgia, we were seeing problems in, the week before that, Pennsylvania and Maryland and the District of Columbia and elsewhere and how they were able to administer the voting by mail processes.

And then of course, the Wisconsin primary back in April is the poster child for the problems in which a number of voters, tens of thousands of the Wisconsin voters probably did not receive the mail-in ballots they'd requested, did not receive mail-in ballots that they had requested in a timely fashion before it was too late for them to cast them. So we'll have an opportunity to talk about what we've seen happen already and the way in which that provides some lessons for us as we work to be prepared by November. So with that as a context, let me just maybe invite Lisa to offer some thoughts to begin on how states might be better prepared to handle a surge in voting by mail interest. Lisa?

Lisa M. Manheim: Yeah. Thank you very much. I think at the outset what I might say is that it really matters in this context who is implementing the relevant reforms. So what you have in election law administration is you have a number of different actors who are contributing to how an election is run. You have the state and local officials. You have the state legislatures. You have the state courts, the federal courts. You have the federal legislature. You have all these different actors working together and combined they produce an election. So when it comes to reforms, these reforms or these changes to an election can run through all of these different entities.

If you have reforms in a context like this running through, for example, a state legislature at the outset, it tends to produce a much better outcome than if the reform is by contrast ... I shouldn't say reforms, but if the changes are being mandated by a court closer to the election. So this relates to just the logistics. If a court, for example, decides that it's necessary to allow a certain type of absentee ballot to be cast, that is not implemented magically. It's really difficult to implement a change like that in a fair and efficient way. If the state legislature or other authoritative body is doing that early in the process, it's much easier and more successful when the administrators on the ground are actually implementing these changes.

It's also much easier, tends to be much easier as a legal matter. So the state legislatures have close to plenary authority over how elections are run. By contrast, a federal court is constrained by a number of different competing and determinate doctrines. Finally, as a matter of legitimacy, again, if you have a state legislature or other authoritative body implementing these reforms rather than a court scrambling at the last minute to respond to problems, it tends to feel more legitimate to those who are participating in the process.

Huefner: That's really helpful. I think it is important to keep in mind the various bodies here, whether it's legislative, administrative, or judicial that each could play some role here. So Justin, I'm going to turn to you next to see what else you might say and whether you ought to talk in some specific terms about things at the legislative level or the administrative level in particular at this point that we ought to encourage or hope might be happening.

Justin Levitt: So unsurprisingly, I'm going to agree with Lisa an awful lot now and throughout. I 100% agree it is unquestionably better, democratically ... I'm sorry. Legitimacy matter also in terms of ease of implementation when the legislature actually makes the rules. The big caveat, and Lisa mentioned it, but this is the important cross-cutting concern is not just the who but the when. If the legislature makes the necessary arrangements to actually hold an election early enough that the administrators can implement, that's the ideal situation. Unfortunately, all too often legislators aren't the ones blamed when the process goes wrong, so might not have an incentive to actually change the system to accommodate new circumstances.

The people on the receiving end of the complaint box are always the local election officials administering the election and occasionally the state executive officials that have to decide whether they're going to allow the administration of the election as the legislature intended. That unfortunate disconnect in the assignment of responsibility by the public sometimes leads to legislative inaction. When we really need the legislature to step up and step early, it is not always the case that they will do so. That's complicated further by perceived partisan intentions. Now I say perceived partisan intentions because I think voting in a time of a pandemic, many people have an instinct about how different election structures are likely to impact different electorates and I think that instinct may be wrong.

That is, whatever your rule of thumb for partisan impact in the normal course of business, the amount of disruption in a pandemic is already so high that further disruption may have entirely unpredictable partisan consequences, so consequences that are really difficult to predict. So individuals who are attempting to game out, if I act, if I don't act, what kind of partisan impact is this going to have, may well find themselves with a lot of unintended consequences down the line as the system begins to break in further and further unpredictable ways that impact voters that they might have had in their head, they might have thought would be more resilient.

So you have sometimes legislators' instinct to defer responsibility because they're not necessarily on the hook. You have perceived partisan consequences that people have internalized and that also lead to incentives to act or not act. What all of that means is although I agree 100% with Lisa that the optimal body is the legislature when it does its job and does its job earlier, as we've seen so far this cycle, it doesn't always happen. So sometimes you need executives or courts to step in to make sure that the fundamental right that we have to vote is actually able to be exercised. The earlier that happens, the better because I want to come back to Lisa's point.

A last minute eve of election change in the rules is not only hard for administers to administrate, it's enormously hard for voters to process.

Huefner: Great. I want to bring Ned in in a minute, but let me ask both Justin and Lisa as a follow-up a little more about legislative action at this point because you've both made the point that that would be the ideal way to stave off some of the potential problems. I think it's accurate to say that state legislatures and many states have made changes this election cycle, although most of what they've been doing has been simply to postpone their primary elections in light of the pandemic. Huefner: But the point is it realistically too late for a state legislature to make a substantive statutory change for the November general election, specifically with respect to things like how voting by mail should be conducted?

Levitt: I don't think it's too late now. I think it's about to be too late very soon. But in terms of both funding for local election offices and substantive rules, particularly the substantive rules about who is eligible to cast an absentee ballot and under what conditions a ballot can be cast if all else goes wrong, that is dealing with provisional ballot structure, dealing with, I know we'll talk about this, an emergency write-in ballot structure, the sort of safeguards for safeguards. When the seat belt breaks, what other safety devices are there in the car?

I don't think it's too late for legislators to be implementing those rules now. But now means the month of June and the month of July and maybe part of the month of August and no later. By the time we get into anything that normal Americans recognize as fall, then it really is too late. Then we have to be on the train to actually implement these laws.

Huefner: Thanks. Lisa, go ahead.

Manheim: Yeah. I like that seat belt analogy. It's sort of like at this point with the pandemic now coming on top of the preexisting problems we had with election administration, it's like the seat belt's not working. The air bag's not working. The driver's trying to pull the car to the left. The passenger istrying to pull the car to the right. We're still trying to keep the people in the car safe. That kind of goes to the point that no election is perfect. At this point, it's pretty clear that no matter what happens these elections are not going to be perfect.

So the question becomes what do you do when you know the election is not going to be ideal? Actually, we have some experience with this. This is just an extreme example of that. One of the things that is perhaps the most important is for people to, on one level, agree on what the purpose of an election is . To the extent that the purpose of an election is to facilitate the right of eligible voters and only eligible voters to participate in the selection of candidates, then it becomes increasingly clear, I think, that the goal for this election needs to be to facilitate the ability to vote really where that is going to be possible.

That being the case, is it too late for the legislature to respond? No, I would say not least of all because there's going to have to be one response or another as we get close to the election. We're still in the period where it would, in my view, pretty clearly be best for the legislatures to be leading this charge.

Levitt: Just to follow up on Lisa's point, courts hate assigning and divvying up resources and that's one of the tools in running an election that can help compensate for the sort of resource constraints, very serious resource constraints. We saw it in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania and Maryland and Georgia. Courts absolutely hate that because they feel probably correctly that they're not experts in figuring out what should be. They can best understand what should not be, but it's very hard for them to build and figure out what should be. Legislatures are really fairly well-appointed for that.

So exactly to Lisa's point, to the extent that provision and reallocation of resources is one of the tools in the box to help the elections go smoothly this fall, the legislatures really are in the best position to make those calls.

Huefner: I'll offer one additional thought and then I'll ask Ned for his reactions. We're talking about state legislatures here and, of course, there are many states whose legislatures are not full-time legislatures. They have, in some states, very small windows to legislate unless they're called into special session. Even for legislatures that are full-time legislatures, they may often regularly be in recess in July or August. So it really is going to be important for legislative change to happen right away in any state that's able to do that.

I've already teed up a number of the things that state legislatures might do, whether it's funding and resources, whether it's clarifying who in fact is able to vote an absentee ballot in their state. We saw fights in Texas where the courts became involved in interpreting whether the Texas law that said you still needed to have an excuse to vote a mail-in ballot would allow the fear of catching COVID-19 be a legitimate excuse, for instance. Legislatures could clarify those issues if they would act as well as finding ways to clarify or streamline other requirements, like witnessing requirements and so forth.

But Ned, we'd like to bring you into the conversation and see what your thoughts are about things that might be happening now and by whom.

Ned Foley: I think Lisa put it exactly correctly when she said we've got to keep our eye on what the purpose of an election is. It's to allow eligible and only eligible voters to exercise the collective choice on who the candidate should be to lead the government for the next period of time. Frankly, I'm worried that this year, because of the stresses of COVID, but other reasons as well, that it's not clear that we're going to be able to hold an election that conforms to that basic standard that we're expected to achieve and usually we do achieve.

I'm more worried now than I was three months ago when COVID started because of the partisan gridlock that is happening in legislatures. I agree with both Lisa and Justin that the legislatures are the place to do this. But for some of the partisan perceptions that Justin is talking about and maybe others, in states where there's divided government as there is in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania and some other states, there's a paralysis. There's just a legislative paralysis that is not good for the voters, not good for democracy and the citizenry.

It's really incumbent on them as the current office holders to get beyond paralysis for the sake of society, but they're doing it. They're running out of time, as Justin said. So we have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst at the same time. As Lisa said, it may be that the legislature is going to be forced into action much closer to Election Day than desirable. It's not desirable to have courts issuing decrees in October about the election, but it's also not desirable to have the legislature changing the rules at the last minute either. But we need to have an election. It's scheduled and it's going to happen one way or the other.

But for reasons that Steve indicated at the outset, the data at the moment suggests that we're not ready collectively, and that's worrisome. Again, the legislature should do now exactly what Justin's talking about, but we need a plan B if they don't.

Huefner: Well, it's worth the brief comment that in Wisconsin back in April, what we saw was a legislature that was being urged to take action in response to what was a looming crisis that refused to do so. It was legislature's refusal there that led to the judicial involvement, both as a matter of state court and federal court cases. Well, so this is all quite sobering to be wrestling with here in June as the primary season is almost over, but not quite, and we still have some time before the general election.

Let's talk for a few more minutes about things that still might be done before we reach that moment in late October when we're in a panic mode. One of the things that does seem possible given that we still have a few months is some dramatic increase in voter education, voter awareness, helping the electorate have a sense of their opportunities and their responsibilities here. Would anyone like to share comment about that option? Justin?

Levitt: Yeah. So really quickly, I think that's absolutely right. People don't generally tune in to the general election, much as I hope it would be otherwise, until after Labor Day. Even that's generally early. We're going to need people to tune in to the process much earlier than that. That is going to take a lot of education by administrators, by nonprofits, by campaign groups about the process. By the way, when the process changes, that takes more education to help people understand what the rules are now rather than what the rules are yesterday.

One of the things I want to highlight is not just education about absentee ballots, particularly in locations that are not used to it. I'm sitting in California. California's had about 50%, 60% in some elections vote by mail in past elections. For us to get our rate up to 80 or 90% is a stretch and a push, but imminently possible given the planning and given the muscle memory that we already have. For some states and cities on the Eastern Seaboard that are used to five or six or seven percent vote by mail, getting up to a significant vote by mail push is a real change, not only for administrators but for voters.

You see some of that in the results out of some of the Eastern Seaboard primary elections that we've seen over the last month or so. In addition to education about vote by mail and about absentee balloting and about applying or filling one out or returning it, there has to be education, and I can't emphasize this enough, about voter registration. About 14% of America moves every year and most of those moves are small and local to another apartment in the same complex, down the street, to another part of the county. When you have a system where you can vote in person at the poll, it is not only possible it's legally required to accommodate small local changes in address at the poll onsite.

Election officials and poll workers know how to do that. When you're working on a system that requires vote by mail when you have to have an accurate current address in the system, it's not possible to deal with any of those changes in the absentee system. That's got to be taken up by voter registration. Voters who are used to fixing it at the polls later are going to have to start fixing it now, start changing their registration, updating their registration. For that, there needs to be an enormous push nationwide to get the rules clean enough to actually be able to run a mail election cleanly in the fall.

Huefner: Whose responsibility is that voter education project? Is it voting rights groups? Is it election administrators? Is it academics? Is it a shared responsibility?

Levitt: Yes. If that list doesn't include everybody, we're leaving somebody off the list. It is voter's responsibility. It is the officials' responsibility. It's community organizations' responsibility. It's society's responsibility. We're in a mode where we have just had to teach each other, all of us, how to stay socially distant, when to wear masks. Sometimes we need reminding. That's a very new process that we are all learning, but we taught each other over the course of two months. Some of us are forgetting now. We'll have to get back to teaching each other again.

But that's a major cultural realignment that we all were responsible for educating each other on and that same sort of thing has to happen with voter registration. It has to be as urgent as Dr. Fauci giving daily updates on how registered we are in order for people to understand they've really got to get the rules in check. That's everybody.

Manheim: As another data point confirming the importance of voter registration in a time of the pandemic, there was a study recently released indicating that across 11 states in April 2020 notwithstanding the general interest in the upcoming election, the number of new voters registered actually decreased by 70, that's 7-0, percent compared with four years ago. So that data point, for me, just helps to confirm what I think we can intuit pretty easily which is that the pandemic is affecting these different elements of election administration across the board.

So I agree with Justin that something that maybe seems like it's not directly implicated by COVID, often there's ways of registering that don't necessarily implicate social distancing. But actually, all of this is affected. Everything's affected. To that end, yet another area of education for people that I think would make sense would be to look at what is likely to change on Election Day and after in light of the increase in mail-in ballots and the other changes associated with the pandemic. So among the likely changes are the following. First, we are unlikely to get returns at the rate that we're used to.

It takes much longer for jurisdictions to count ballots when they're coming in all different ways and when they're being submitted by mail, particularly if the deadline for receiving those absentee ballots is after the date of the actual election. So the ballots, while they're cast on Election Day or earlier, oftentimes a jurisdiction will allow them to be received after Election Day. So that's one change. It doesn't go to the legitimacy of the election. It's a predictable consequence of the changes that we're seeing. A second consequence is that for better or for worse, if an apparently losing candidate wants to challenge the apparent result of an election, absentee ballots can give somebody a number of different additional legal rounds to try to challenge an election.

I would anticipate both because the upcoming election is sort of highly contested. Because of polarization but also because of these various changes, we're likely to see quite a bit of post-election litigation.

Levitt: I just want to emphasize something because I think this can't be said enough. Lisa said it. I want to say it again. I'm hoping Ned says it again. I'm hoping Steve says it again. This is also education for the public. Lisa's absolutely right. The returns may take a while to process and that doesn't mean anything was wrong. That means it's working, not that it's broken. Unfortunately, in a Twitter moment, in a cable news moment where thereneeds to be something to fill the airtime, the initial instinct may be we're used to seeing the election countdown clock count down eight minutes till poll close, seven minutes till poll close, one minute till poll close.

And then as soon as the polls close, a winner is called. Now, we in the election world know, we in the legal world know the winner's not called until the election's certified, and that's weeks after the election. But for the public, they expect a winner to be known the minute the countdown clock goes down to zero when the polls close. That's very unlikely to happen this year. That does not mean that something went wrong. That's something that's going to be incredibly hard to explain to the public but, again, that needs to be nationally known and recognized and we need to start that now.

Huefner: Well, and let's be clear that the primary reason that certifying the results takes some time is because the election officials are taking appropriate steps to make sure the count is accurate. In particular with respect to mail-in ballots, there is a process by which each individual ballot is verified tomake sure that it is coming from an eligible voter. That is a more cumbersome process. Pre-COVID, there were reasons to want to be favoring in-person voting over mail-in voting for a number of reasons. We now live in a new world where voting in-person has risks we did not anticipate before.

Given that, the question is how to best balance a range of risks in order to facilitate voting by everyone who desires to vote. But as you observed and Lisa observed, there will be more opportunity for litigation about the results as well because of the way in which each one of those absentee ballots itself can be the subject of a contest. I think I saw Ned's ready to share some thoughts about that as well. I mean Ned has given a lot of attention to the way in which these kinds of issues can play out in a post-election contest environment. So Ned, let me offer you a chance to react.

Foley: Sure. Thanks. Justin's right. I will add, I wish I could repeat verbatim what he just said echoing Lisa, so add my voice to that chorus on it's not a flaw. It's the way the system is working to have a late count if you're relying on ballots that can't be counted on election night. It's just a part of our new reality. But I'd like to go back before we focus on the counting process to just underscore the distinction that we are talking about two different challenges at the moment. You asked what should we be doing right now so that we don't have to do quite as much maybe late October?

I would distinguish in my mind analytically between the challenges that involve the casting of ballots on the one hand because people actually have to vote those ballots in order for them to be counted. And then we'vegot some challenges with respect to the counting process which, in my mind, is analytically distinct. Both need to be addressed to some extent now, but also a little bit in different ways with different challenges for the system. So as I look at the challenges involving the casting of votes, the biggest one in my mind is just a sheer capacity issue that's been stressed by the virus. The primary stressor is on the vote by mail side given the exponential growth and demand among voters to want to vote a mail ballot, as they are entitled to do in so many jurisdictions.

Right now the evidence is showing that local officials cannot handle that capacity demand. So it's a logistical challenge as much as a legislative one. They need money in particular and resources. As much as peoplewere talking in Wisconsin about utilizing the National Guard for purposes of poll workers who are missing, we might need to utilize the National Guard just to process absentee ballot requests because the local jurisdictions are not capable of keeping up with those absentee ballot requests.

One legislative idea to consider, frankly, but it might get pushback from the voting rights groups is actually to change the deadline for when you have to apply for absentee ballot and actually make that deadline earlier, sooner rather than closer to Election Day. Our tendency is to try to write the rules that are favorable to voters. But frankly, right now we're giving voters false expectations. The experts on absentee ballots, people like Tammy Patrick who have administrative experience running this thing, that we're setting our system up for failure by the existing rules that say you can wait until a week before Election Day to apply for an absentee ballot.

Well, the post office can't handle that. The administrators can't handle that.We need to solve that problem one way or the other. I'm personallyagnostic as to what the right way to do it is, but all ideas should be on thetable for consideration, recognizing of course the window for legislative changes is closing rapidly. But we have to solve that capacity problem one way or the other. And then even though it concerns in-person voting, we have to acknowledge that we have this huge poll worker shortage. The reason why that's important, even with respect to vote by mail, is if voters don't get their absentee ballot that they're entitled to vote because of this capacity failure to give them their absentee ballots, we saw this in Wisconsin.

You had people going to the polls because they never got their requested absentee ballot, causing the lines at polling places on Election Day to be astronomically longer, which was another capacity failure. We're not at capacity at the moment. We still have a few months, but we have to work very quickly because otherwise we're not going to be able to put a ballot in the hands of everybody who's entitled to cast one. If we don't do that, we've got disenfranchisement.

Huefner: Let's keep talking about the capacity issue for now. I know, Justin, you wanted to weigh in.

Levitt: Yeah. Just very briefly and that is, I know that we're talking about the absentee system now, but Ned just mentioned it and I don't want to let it go. It's fine to be talking about that. There are plenty of problems to be resolved in that. All of this comes with the expectation there will also be at least some in-person voting capacity. There has to be. There are some communities where we're used now to thinking of hard to count communities in the census context. There's some communities that are hard to mail, Native American reservations, for example, some urban environments.

Postal delivery doesn't always get the right ballot to the right mailbox. Those communities in particular need in-person voting options. Disability access and language access and other communities that want assistance, very hard to get help with an absentee ballot from an official at home. But if you go to the polls if you're able to go to the polls, that provides an option. That's all on top of the cultural preference of some communities to vote in-person in groups at the polls, which the pandemic is really putting a stress on. I know we want to continue talking about the vote by mail system.

But it's really important for folks listening to know that just because there is attention to the vote by mail system, does not mean that people don't also have the [inaudible 00:35:42], exactly like Ned mentioned, that there is adequate in-person capacity. That's going to need location and poll workers, both of which are in short supply.

Huefner: Lisa?

Manheim: One example of an attempt at responding to these problems that seems overall to have been successful came recently out of Iowa. In a sense, what the election administrators did in Iowa was expand the opportunity for absentee ballots quite dramatically while at the same time in a sensible, careful way shrinking the opportunity for in-person voting. By taking those two approaches at the same time, what came out of that experience overall appeared to be a success. You had record turnout in that primary election in Iowa. You had also had dramatically more people vote by absentee ballot in Iowa.

One of the things that I take out of that illustration is that the administrators really decided to look at the trade-offs and put those resources towards absentee ballot voting. For example, they sent out an absentee ballot application to every eligible voter, but then again, dramatically reduced the number of polling places so that the polling places that were open could be properly staffed and run. Now, at the same time that this, to me, feels like a bit of success story under these trying circumstances, there's also a troubling coda. That's that the Iowa legislature in response to this experience has begun the process of passing a statute that would actually reverse a lot of these changes.

So in my mind, this Iowa example both shows the potential for what a jurisdiction can do, but also helps to remind us that the challenges here are not simply logistic, but they're also political.

Foley: Can I jump in and ask whether or not all of us or how all of us feel about a possible legislative change that at least could be considered and, frankly, if not adopted by a legislature, could be considered by a court as a second best idea? Better to have the legislature do it if that's the right thing to be done. That is it goes back to this capacity issue and what if we don't solve the problem, the plan B question that I'm particularly worried about? Given the fact that Wisconsin was not isolated, we saw this again in Pennsylvania and Georgia, a number of other states where, as Steve said, at the outset, we've got voters who did everything right.

They properly requested an absentee ballot and they didn't get one by Election Day. You can't vote a ballot that you don't have. So what's the solution? For military and overseas voters, Congress adopted a solution in order to prevent disenfranchisement because we don't want the soldiers and sailors defending the nation to be disenfranchised because they never got the ballot that they properly requested. So we have an emergency backup ballot that Congress says must be available if the regular ballot doesn't arrive on time. I understand why it's an administrative complication to try to expand that beyond the scope that currently exists for military and overseas voters.

But I also really don't like the idea of disenfranchising eligible voters and have an election be maybe turning on who is disenfranchised and who isn't. So I'm open to other solutions to solve the disenfranchise problem. But we've been witnessing massive disenfranchisement in this primary season this year and I don't think we've solved that problem yet. I think it needs to be addressed either legislatively or judicially because I don't think the level of disenfranchisement that we're seeing is tolerable in a society that's devoted to the principle that Lisa correctly identified, which is an election that allows the voters who want to vote, the eligible voters who try to vote to meet that standard, because we're not meeting that standard right now.

Huefner: So Lisa and Justin, I know you each have some thoughts about this kind of emergency backup. Lisa, why don't you lead?

Manheim: Sure. If I understand the idea here, the idea would be to take the ballot that we already have that essentially is blank and to offer this ballot to people who have requested an absentee ballot but have not received it in time. Now, there are two incredibly strong points to recommend this approach. The two points are the following. First, in response to what in a way is the worst problem you can have in the field of election administration, which is that you are not allowing eligible voters to vote even though they have done everything they were supposed to do in order to vote.

So it is responding to the most severe problem that exists, in a sense. It has a lot to recommend it because there's precedent for it. We've been doing this with respect to certain military voters and overseas voters for a while and so there's some protections against manipulating the system. There's some understanding of how this all works. So those are two really, really strong points to recommend this. I would say that basically everything else is incredibly problematic about this approach. So where does it fall out in the end? I don't know. This may be the best approach because we're in this 12th best world.

But some of the problems with this is that it's burdensome for poll workers to deal with this ballot. It causes timing problems in terms of some of the issues we've already talked about and also in terms of counting the votes afterward. Perhaps the two biggest problems I see here are first that it worsens some of the inequities that we already have in the system. So if I understand how this works, I'm not sure that voters necessarily would be able to cast these ballots unless they each have a printer, which is something that as somebody who only got a printer in the last few months at her house, I can tell you not everybody has a printer.

Also generally speaking, I think you have to have a stamp for these ballots unless we find some way of giving pre-postage. Again, not everybody has a stamp. You also need to have enough knowledge of the candidates to be able to write in in a way that's going to get counted who you want to vote for. Now, is all of this an insurmountable hurdle for a lot of voters? No, but it's going to be an insurmountable hurdle for a lot of voters. Generally speaking, it's going to be the same groups of voters that already are experiencing a lot of challenges voting.

The final big category of concern about this would be about the legal effect of these votes in the circumstance of a close election. These votes are going to be ripe for the taking in terms of the candidates if in a post-election dispute pushing back on them. Therefore, if somebody decides to cast a ballot this way instead of going in-person and just trying their best, then it is I would say entirely possible that this person's vote will end up not counting in a post-election dispute. So in a sense, I hate this proposal but I think it might be the best one, which is kind of where we are right now.

Huefner: Thanks. Justin?

Levitt: It's kind of hard to add anything to that magnificent summary. I agree with every word of it. I'll point out two other cons and they come out in exactly the same place that Lisa is. One other limit of these ballots, the federal write-in absentee ballot, the FWAB, and FWAB may be the worst acronym you could possibly come up with but it's familiar at least. One other limitation is it also exacerbates a different inequity and that is Americans' fixation on the presidential election to the exclusion of everything else.

If you have a blank ballot, and Lisa's absolutely right, it's just a ballot with the federal office and then all others. People will tend to write in the highest profile choice of candidate, that's going to be the president, and tend to forget absolutely everybody else who's running for election. That's a real problem if it leads to a degradation of the importance of all of the other offices on the ballot which we have on the ballot for a reason. Also, as Lisa mentioned, the inequities, if you have a printer, if you can get to a post office, if you had a stamp, if you have all of these things and, as she says, not everybody does.

It also makes these ballots not only later, but harder to process. They're not on uniform card stock. They have to be essentially hand counted. That's fine when it's a couple thousand. It's really hard if it's a couple hundred thousand. So like Lisa, I see some real limitations with this approach, and they may be the best of all available really bad options at this point. So I come out in the same place she does and the same place Ned does. In a normal election, I think of the work that we do as election lawyers as trying to put duct tape on the bucket to keep the bucket from springing aleak.

You're looking for enough duct tape to cover up the hole. In this election, I'm trying to find enough duct tape to make a bucket in the first place. There's no bucket. We're just trying to create something that holds water out of duct tape. In that world, it might well be that when all else fails, having the opportunity to vote with this emergency ballot is the best that we've got. I very much appreciate Ned's point that you can't vote a ballot you don't have. So at the end of the day, if it's the choice of this or nothing, the answer's got to be something like this emergency absentee ballot.

As Lisa points out, the litigation will also inevitably focus on this. So if you're looking for legislative action, legislative validation of these ballots as a last resort early is going to be incredibly important. Ned, I know that'spart of why you bring this up now. Among the changes that legislatures should very strongly be considering and the courts should very strongly be considering ordering now to make sure the litigation's out of the way before the election is to leave this as an option, as a worst case option, as a best worst case option so that we can make sure it's a legal option before Election Day.

Foley: If I can just add to that, and I appreciate what Justin just said, I think the reason to discuss this now is to try to fine tune the idea so that it's least bad. In other words, if we don't like the idea that it's blank, maybe there's a way to get it to look as much like a regular ballot as possible as opposed to just the generic ballot that's available to the military. I mean if you're going to have to print a ballot somehow, why not print a real ballot with all the candidates that are appropriate for that particular precinct rather than force the voter to essentially do a homemade ballot?

But today I still believe a homemade ballot is better than no ballot and I'd like to make something better. If voters themselves don't have printers, figure out how to do that. I also think both Lisa and Justin are correct that,again, we need to think about the interactive relationship between the vote at home option versus the vote at a precinct option in a COVID world because I do think there are some voters who would prefer to vote at home but don't face such health risks that if we do precinct-based voting correctly, that should be a reasonably safe alternative.

For other voters though, no, they can't go to the polling place. So they've got to have some vote at home option. So I think, again, I think a lot ofwork needs to be done fast on how to think this through, again, hopefully by legislation or administrative direction as opposed to a judicial decree in October. Lisa, to your point though, I'd like to say one thing. Both you and Justin are correct that there might inevitably be litigation over this unless it's cleared up legislatively ahead of time, just the nature of our litigious society in elections. But if we think through this issue properly and in a nonpartisan way with the principle that you, again, stated at the outset about how we run an election where every eligible voter and only eligible voters get a genuine opportunity to participate.

Even if we have an understandable initial resistance to count homemade ballots or ersatz ballots or ballots that we aren't really used to, again, if the alternative is disenfranchising an eligible voter, I think you can make an argument to the judge. Frankly, I think the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which talks about provisional ballots, we have come to understand the concept of a provisional ballot in a very narrow technical sense because there are elements of how does it speak to the more technical element of it. But how to use the term fail-safe voting to get at the concept. It was adopted because people went to the polls in Florida in 2000 who were perfectly eligible, but they had been erroneously purged from voter rolls.

They were turned away empty-handed and how there was a Congressional statement, "Never again." We are never again going to disenfranchise valid voters who turn out, who do what they're supposed to do. We worry about low turnout rates. We've got voters turning out and we don't want them turned away. That's what happened in Georgia in June of this year. We've got to solve this problem. I don't care whether we call it a provisional, a FWAB, a fail-safe ballot. We got to give every voter a ballot, how I think it's a matter of federal law can be construed to require that already.

If states and locals are failing to do that and we've got documented voters who are disenfranchised, we've got to have a remedy.

Manheim: All that makes sense. I think I would have two responses to it. One actually circles back to your point. I think it was your point. I'm sorry. I forget exactly who said it. But the point about maybe in this election it makes sense to cut off the absentee ballot application form early. The reason why is not because we want to preclude people who are thinking about this closer to Election Day from getting an absentee ballot, it's because we don't want to give false hope. So that's actually where I would go to here. If you say to someone, "Look, this line is so long. Here's a write-in ballot. Just do it. Give it to me. Hand it in and go home."

I do worry that you're going to have some voters who say, "Great. I just don't want to be doing this anymore." They would trust that this vote would count. I can tell you from my experience, I don't trust that the vote would count. It might, but it might not. It really depends on a lot of different factors, including the rules of the state that you're voting in and the judiciary in that state and then what the federal courts do in response. To that end, I would actually go to that question, which is what are the courts going to do in response to this, in response to some of these other issues and to further confirm that it is really suboptimal to rely on the courts to be fixing these problems?

I tried to figure out what the federal court response would be to this argument that given late-breaking problems, let's say, at a polling place or with absentee ballots, voters are required to be offered the option of these write-in ballots. I'll tell you, I study this and I can't tell you whether the court would say on the one hand, yes, it's required under federal law that you give them the absentee ballots. Under federal law, it's prohibited that you change the rules at this point and offer them the absentee ballots. Or if they would say this is not a federal question and the state can just decide.

We really don't have settled enough law in this area to rely on what you're suggesting would be the best outcome. Although I completely agree on the merits. I just worry as a practical matter that this would give false hope to some voters. Still might be the best option.

Huefner: If it might be the best option, that leaves open the possibility of some other options even if we're not as hopeful about them. What are some other options as a plan B at the moment at which there are voters who have done all they are supposed to do and yet do not have a ballot?

Levitt: I mean some of those other options involve making sure that there is in-person capacity. This comes back to the prior point. There's only so much you can require. You can't require poll workers to show up who don't want to show up. You can't require locations to exist that don't want to lend their space or they can't lend their space. So we're basically talking about last-ditch efforts to make sure that when it's two days before Election Day, a voter knows how he or she is going to be able to cast a ballot.

If the regular absentee process doesn't work, we need some emergency remote process. That's the emergency ballot that Ned just talked about. If that doesn't work, we need some opportunity to vote in person and there aren't ... I mean I can tell you. Election administrators are trying really hard to set aside space and time and resources to make sure that that exists, but you can't just conjure that out of nowhere. That's where some of this money actually is so very important to make sure that administrators can rent space if they can't borrow it or beg it to ensure that they actually have locations, to make sure that they can pay more than minimum wage to a poll worker who's willing to sit there in a time of pandemic and access ballots and let the voters vote.

The other thing that we can do is, frankly, encourage more out of society in providing help for these resources. We are very used to requiring government to make decisions about how to allocate resources in this way. That's the standard process for facilitating voting is it's a government process and the government decides on budgets. There are all sorts of failure points along the way to getting election administrators the money they need. There is a provision of federal campaign finance law that expressly and explicitly allows corporations and unions, two entities that we think of as not having a lot of role in providing money into the process beyond advertising, to give money to local election officials to help them with registration, voting information, and forms at the least.

That's something that I would also hope would be out there. These are tough financial times for everyone, but there are still entities with more resources than individuals have and sometimes more vote power than local governments have that may be able to really facilitate the provision of local space on Election Day. We should be encouraging that as strongly as possible.

Huefner: Thanks for those additional possibilities. I know Ned also was ready to weigh in. I know we're running out of town. Let me throw one more idea into the mix and then we'll all have a chance to continue to talk for a few minutes. I know that there are some locations that faced with the kind of problem we're discussing have taken advantage of electronic communication to send out ballots, which would not be their norm. I mean there are some states where that may be the norm, but I'm talking about states where that's normally how they transmit an absentee ballot to the voter who's requested it.

To what extent might that also be a partial solution or another piece of duct tape on our bucket? I can imagine some pros and cons with electronic mailing, so I just put that additional one on the table. Ned, I know you were ready to say something, probably not about that.

Foley: Well, on that point, again, I'm open to all ideas for what the best plan B is. I think in recognizing that people don't have printers, I think is an important point. I'm not at the point where I'm comfortable with voters electronically returning their voted absentee ballots, a form of Internet voting. I wish we had the security to do that, but I'm not comfortable with that. That doesn't seem to me like a feasible plan B. Electronically making available an absentee ballot that isn't just blank but actually looks like the voter's actual ballot and having that electronically accessible, I think that's a great idea.

The question as I understand it is whether the voter can do on their own initiative as a self-help mechanism or instead needs these overworked and overburdened local election officials to give them some key, be it electronic or otherwise to open that electronic box. If the voters are relying on the local administrators to do that, I think we're back to the original problem because they've already asked the local administrators for their official absentee ballot to be sent to them and the overburdened official's having done that. So I think we need to look for a realistic self-help mechanism that doesn't require overburdened local officials to do something because that's the same problem to begin with.

If I could just make a large conceptual point that goes to our earlier conversation about, again, what's the standard for judging a successful election or, worse, a failed election? I think it's really important to realize that we're going to get a tally in the certified result. There is going to be a number that says one candidate is the winner and the other candidate is the loser. Obviously, the candidate that's favored by that tally is going to say, "It's a great result. I'm the winner." But as a society, we have to ask ourselves, "Is it a genuine tally? Is it a real result? Does it actually conform to the participating electorate?"

In a world where disenfranchisement is potentially outcome-determinative, the reported tally isn't necessarily a genuine tally and we're just fooling ourselves if we think it is and treat it is. So my view, it's really a sham election if we say we have a winner because we've got this vote tally, but it's just contrived. It was contrived based on disenfranchisement. The problem that I'm worried about is because of differential access to the ballot, depending upon whether you live in an urban location or a rural location or a suburban location. We could have this asymmetrical effect where disenfranchisement doesn't fall randomly and evenly across the electorate but, instead, is consequential.

And then again, we have to ask ourselves the hard question, do we just accept ... Lisa was absolutely right. There is no perfect election. We will not have an election with zero disenfranchised voters. I hate to say it. I really feel for any voter who is wrongfully disenfranchised. To me, the systemic question is whether the disenfranchisement has caused a failure to identify accurately the winner that the electorate collectively wanted of the eligible voters. I think that's the test, if it comes to it, for a court to assess. That actually draws on the ALI project that this podcast grows out of.

Huefner: I feel like we have managed to air quite a number of possibilities, not all of them encouraging, but with some realism about the ways in which as a system election operations in each of the states might respond. Because we're about out of time, I'm going to just invite each of you to offer any concluding thoughts you might have, recognizing that we are in a world in which we will not have a perfect election. We've always been in that world. But we are in the same world with now a much more complicated set of considerations.

Huefner: It's about balancing risks in a way to maximize the chances of producing the kind of outcome I just described. So with that, final thoughts, Justin?

Levitt: Just that I would hope that all actors are able to keep in mind the starting point, the starting principles that Lisa mentioned really, the most important ones, which are that we want eligible voters and only eligible voters to be able to cast ballots that are counted. If that is the lodestar, if that's the guiding point for all legislation and all administrative action and all of judicial action, that's going to be an election that we should all be able to say was a success or at least cleared the threshold of success even if it is not perfect.

That in my mind is more important than having the rules set far ahead of time where the two of those things conflict. We obviously want all of the above. We want the rules clear so that administrators can administrate and we want to make sure that everybody gets enfranchised who's eligible to be enfranchised. Those things aren't [inaudible 01:02:26]. Occasionally that means that the rules that we have need to change, sometimes even at the last minute. Courts should not be so loathe to any change in the process that they forget the point of the election in the first place.

So I think the need to ensure that even late-breaking changes stick by the guiding points that Lisa pointed out first is going to be something that we're going to have to push the courts to consider in order to have an election that we can actually recognize as expressing the true preferences of the electorate. This isn't a game. This isn't a sport. It's a decision about who governs us and it's really, really important that we build the election to make sure that we have the best understanding about who should govern us based on who we prefer rather than artificial rules that are artificially set ahead of time.

Huefner: Lisa?

Manheim: I think in response to what some of the folks on this call have said, I might say something looking backward and then looking forward. In terms of looking backward, Ned totally appropriately voiced frustration and concern that the election going forward won't represent the will of the electorate in the way that feels legitimate. That being said, if you look to the history of elections in this country and particularly if you were to look at the experiences of, for example, people in certain racial and ethnic groups and what voting has been like for them through time.

The possible disenfranchisement that we're seeing in the 2020 elections is deeply, deeply problematic, but it's not as bad as what we've seen in the past. As a country, if we accepted the results of elections that took place inthe 1800s, if we accepted results of elections that took place in the 1950s, I would say that the default is to accept the results of an election that's going forward even under these really, really problematic circumstances. And then going forward, I would say that it is too late by far for the 2020 elections for everyone to look over to little old Washington State in the corner.

But there's a number of states now, including the one where I'm in, where voting is done all by mail. That's actually not quite true. There are limited options for people to vote in person. But everyone who's a registered voter out here in Washington state, to my understanding, received the equivalent of an absentee ballot. You vote at home. You turn it in. If we look to that measure of success, it has been quite a success. Turnout is very high in Washington state, relatively speaking. For those who might be concerned that this is giving rise to opportunity for fraud, a recent study said that out of 14.6 million votes cast by mail in the 2016 and 2018 general elections in three states doing this universal by mail system, officials identified fewer than 100 possible cases of double voting or voting on behalf of a deceased individual.

Manheim: So that's .0025% where there's this sort of concern that's been identified. So again, going forward, this isn't going to be the last election. It might make sense for jurisdictions to start looking to where there has been some success, really leaning into the vote by mail process.

Huefner: Ned, final thought?

Foley: Real quickly, I definitely appreciate Lisa's reference and reminder about history and the awful history of disenfranchisement that we've had in our country. But I guess I would say just because we didn't meet our own standards in the past, I mean we should still try to meet them now. I also think that starting with the Voting Rights Act in 1965 and also the constitutional jurisprudence of one person one vote that came at that same time, we've had a national collective commitment of one person one vote that all adult citizens have equal rights of participation.

I think the question is can we meet that standard this year? We ought to hold ourselves to that standard and, again, try to do it where we can do it pursuant to plan A without the need for plan B. But if we fail to meet that standard of giving every eligible voter the opportunity to vote, then we have to honestly say we failed at our national commitment that we've made to ourselves since the adoption of the Voting Rights Act. I hope we don't have to say that about the election this year.

Huefner: Well, Justin, Lisa, and Ned, this has been both really interesting and very instructive. Thank you, all three of you, for being with us today.

Outro: Thank you for tuning in to Reasonably Speaking. Visit ali.org to learn about this important topic and our speakers. Don't forget to subscribe so you never miss an episode. Reasonably Speaking is produced by The American Law Institute with audio engineering by Kathleen Morton and digital editing by Sarah Ferraro. Podcast episodes are moderated by Jennifer Morinigo and I'm Sean Kellem.