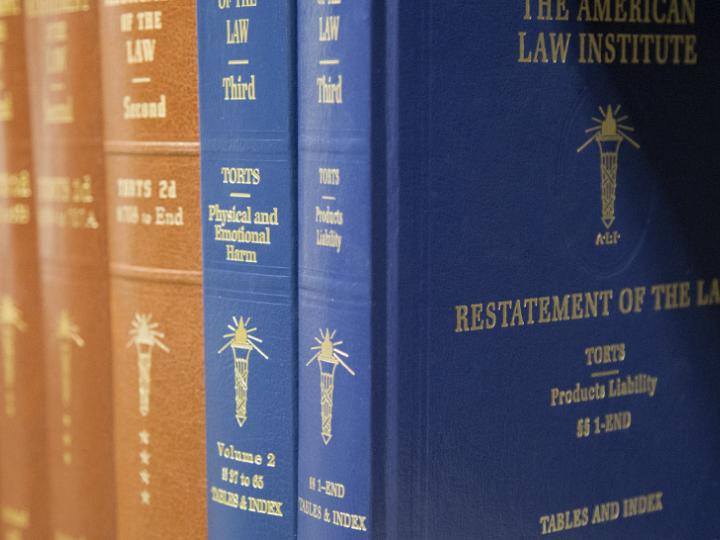

In a recent U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Air & Liquid Systems Corp. v. DeVries, No. 17-1104 (March 19, 2019), Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, and Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, writing in dissent, cited the Second and Third Restatements of the Law, Torts.

In that case, families of deceased U.S. Navy veterans who had purportedly been exposed to asbestos on U.S. Navy ships brought an action against the manufacturers of equipment used on the ships that “required asbestos insulation or asbestos parts in order to function as intended” and that, when used as intended, could “cause the release of asbestos fibers into the air,” alleging that the defendants were negligent in failing to warn of the dangers of the asbestos and that the veterans developed cancer as a result of their exposure to asbestos. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania granted summary judgment to the manufacturers under the bare-metal defense, finding that the manufacturers were not liable for harms caused by later-added, third-party parts, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit vacated and remanded, holding that ‘“a manufacturer of a bare-metal product may be held liable for a plaintiff’s injuries suffered from later-added asbestos-containing materials’ if the manufacturer could foresee that the product would be used with the later-added asbestos-containing materials.” The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the Third Circuit’s judgment to the extent that it required the District Court to reconsider its prior grants of summary judgment to the defendant manufacturers, although it did not agree with all of the Third Circuit’s reasoning.

The Court held that, in maritime-tort cases, “a product manufacturer has a duty to warn when (i) its product requires incorporation of a part, (ii) the manufacturer knows or has reason to know that the integrated product is likely to be dangerous for its intended uses, and (iii) the manufacturer has no reason to believe that the product’s users will realize that danger.”

Writing for the majority, Justice Kavanaugh cited the Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm, and the Restatement of the Law Second, Torts, for basic tort-law principles:

Tort law imposes “a duty to exercise reasonable care” on those whose conduct presents a risk of harm to others. 1 Restatement (Third) of Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm §7, p. 77 (2005). For the manufacturer of a product, the general duty of care includes a duty to warn when the manufacturer “knows or has reason to know” that its product “is or is likely to be dangerous for the use for which it is supplied” and the manufacturer “has no reason to believe” that the product’s users will realize that danger. 2 Restatement (Second) of Torts §388, p. 301 (1963–1964).

The Court noted that there were three approaches on how to apply the “duty to warn” principle when the manufacturer’s product required a “later incorporation of a dangerous part in order for the integrated product to function as intended,” and explained that, under the appropriate approach, “foreseeability that the product may be used with another product or part that is likely to be dangerous is not enough to trigger a duty to warn. But a manufacturer does have a duty to warn when its product requires incorporation of a part and the manufacturer knows or has reason to know that the integrated product is likely to be dangerous for its intended uses.” Citing Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Liability for Physical and Emotional Harm § 7, Comment j, and Restatement of the Law Second, Torts § 395, Comment j, the Court explained that “a rule of mere foreseeability would sweep too broadly,” and rejected the bare-metal defense put forth by the manufacturers, citing the Restatements:

In urging the bare-metal defense, the manufacturers contend that a business generally has “no duty” to “control the conduct of a third person as to prevent him from causing physical harm to another.” Id., §315, at 122. That is true, but it is also beside the point here. After all, when a manufacturer’s product is dangerous in and of itself, the manufacturer “knows or has reason to know” that the product “is or is likely to be dangerous for the use for which it is supplied.” Id., §388, at 301. The same holds true, we conclude, when the manufacturer’s product requires incorporation of a part that the manufacturer knows or has reason to know is likely to make the integrated product dangerous for its intended uses. As a matter of maritime tort law, we find no persuasive reason to distinguish those two similar situations for purposes of a manufacturer’s duty to warn. See Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability §2, Comment i, p. 30 (1997) (“[W]arnings also may be needed to inform users and consumers of nonobvious and not generally known risks that unavoidably inhere in using or consuming the product”).

In his dissent, Justice Gorsuch agreed with the Court’s rejection of the foreseeability approach applied by the Third Circuit, but disagreed with the new three-part standard put forth by the Court. In arguing in favor of the traditional common-law rule, he explained that “it is black-letter law that the supplier of a product generally must warn about only those risks associated with the product itself, not those associated with the ‘products and systems into which [it later may be] integrated.’ Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability §5, Comment b, p. 132 (1997).” Citing Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Products Liability § 5, Comment a, Justice Gorsuch argued that, while placing the duty to warn on a product’s manufacturer incentivized it to provide adequate warnings, placing that duty on others would “dilute the incentive of a manufacturer” by allowing others “to share the duty to warn and its corresponding costs.” Justice Gorsuch also pointed out that some of the manufacturers in this action, which had provided the Navy with equipment that contained asbestos at the time of the sale, rather than “bare metal,” had a duty to warn as well, and quoted Restatement of the Law Second, Torts § 402A(1)(b) in reasoning that, under traditional tort principles, that duty to warn arguably did not stop once the Navy replaced the original asbestos parts with parts supplied by others.

The opinion can be found here.